In Conversation with Rob Imhoff

I have been privileged to enjoy life as a photographer and filmmaker. Early in my childhood, I aspired to work for the United Nations in a capacity that would allow me to travel the world. To engage globally with humanity, explore different cultures and meet many people, regardless of their colour or creed. Little did I know that photography and filmmaking would give me that opportunity.

My life changed dramatically when Melbourne hosted the 1956 Olympic Games. The nation paused to celebrate a momentous occasion and my parents presented me with a key that would open the door to the remainder of my life. I was given my first camera, a hand-me-down Kodak Brownie Box camera that allowed me to begin capturing memorable moments.

At Eltham High School my art teacher, Kevin Engish, had a profound impact on my life. Engish, along with the support of the strong local art community that included names such as Jorgensen, Knox, Skipper, Peck and Burstall all played an important role. Engish coerced me into understanding basic design elements and imparted on me an appreciation for a variety of visual arts. For a couple of years, I studied and debated in-depth such subjects as Renaissance Art, the Bauhaus and Cubism. I was subconsciously being led to my destiny.

Photography to me has always been about connection. It is a deeply expressive way to communicate one’s feelings of a subject. A photograph can be an instantaneous capture of one’s immediate thoughts or it can be the result of an arduous passage over hours, days or even weeks!

Throughout the pursuing decades, photography allowed me to mix with the wonderful tapestry of humans that make this world what it is. I have been privileged to meet, greet and photograph members of the Royal Family, stayed in an Asian Royal Palace where I acquainted myself with a King who shared my passion for photography. I also had the privilege of photographing many noted and talented individuals in the arts, business and sporting arenas. Importantly I was also able to spend endless and joyous extended time with those that are less fortunate, people who joy and happiness emanated from as they endured their own difficulties in life.

Photography has allowed me a passage-of-life that few individuals get to experience, and for that I thank an eclectic array of individuals that mentored and guided me along the way. The passage has taught me to value compassion and empathy not only for the myriad of humans that I have encountered, but also the vast and varied animal kingdom and the unique and varied natural environment that they co-exist in.

Tell us about the top 6 highlights in your extraordinary career as a commercial photographer

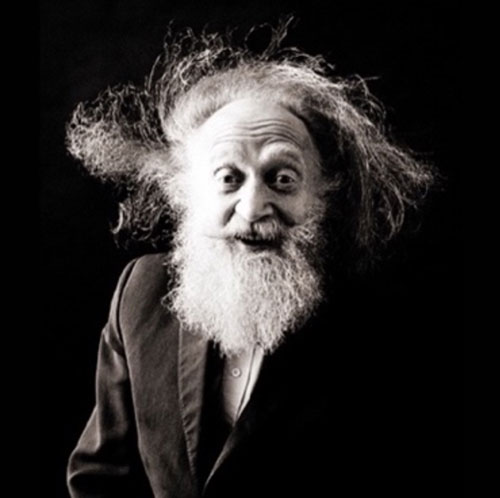

1 – 1969, Portrait of the English actor Sydney Charles Bromley.

At the time I was working as personal assistant to leading Australian photographer Brian Brandt. Brandt was unable to accept the Bromley brief, and suggested that I should do it. Opportunity had knocked on my door and I was going to make the most off it. With little time to ponder the outcome I was confronted by the reality, a portrait was required, and it had to be done now! Spontaneously I was swung into action and had to draw on all that I had learnt as a student, and in my short time as an assistant. Little did I know that this portrait would become one of my signature images.

2 – Association with the British photographers Brian Duffy and David Bailey.

In 1975, while on assignment in London for Mercedes-Benz, Australian expat Bob Marchant who at the time was the art director responsible for the Mary Quant account, suggested over lunch that he take me to meet Brian Duffy at his Swiss Cottage studio. After being introduced to Duffy’s wife, June, I was directed along a hallway where, to my surprise, I was greeted by an old friend, the Australian-born, international model Jill Goodall. Goodall had just completed hair, make-up and wardrobe in readiness for a Duffy shoot. On completion of our embrace, she had to have it all done again! Consequently, Duffy was not a happy man and, when Bob Marchant introduced me as Rob Imhoff, Duffy sharply responded, “No! Fuck off, Imhoff”. Later that evening, Duffy joined Marchant and me in the local for a few pints and, during conversation, Duffy explained that David Hemmings’ role in the 1966 British–Italian film Blow-Up was based on himself. In the following weeks it became obvious that the London-based trio of Brian Duffy, David Bailey and Terence Donovan all played inspirational roles in the script development of the film. Blow-Up had a profound impact on my generation of photographers.

I was to cross paths in later years with both Duffy and Bailey as we completed various assignments for Singapore Airlines – all for the Singapore-based agency, Batey Ads.

When in Singapore, Duffy would inquire with the agency creative if they still used “…that Australian-based Russian photographer”. When asked for more details, Duffy would tease, “You know the one, Fuck off… Fuck off Imhoff!’

3 – Dinner with Arnold Newman and his wife Augusta.

In 1983 I had dinner at ‘Tolarno’ restaurant in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda with the acclaimed New York photographer Arnold Newman and his wife Augusta. During the meal I asked Arnold a question that nearly made Augusta choke on her food. She quickly responded to me, “Don’t go there! … It’s a sensitive issue, Rob.”

Out of interest I had asked Arnold, that, “If he had not been in America and had not had access to names such as Kennedy (JFK), Monroe, Stravinsky, Picasso, etc., would he have the profile that he had today?”

My question to Arnold was not meant to hit a sensitive cord, as Augusta had thought. It had been pertinent to my own career. I went on to explain to Arnold that I did not believe I would personally build an archive of world-famous American images as he had. Nor, of world-famous English images as our friend, the British photographer Brian Duffy had. I explained to Arnold that I intended to build a personal archive of images based on my life as an Australian photographer and filmmaker.

Dinner with the Newman’s had a double edge interest for me. Arnold and I would exchange banter about photography and Augusta (Gus), and I shared a common interest in local government issues and the welfare of our residential precincts. While Gus’s interest was in Manhattan and mine in South Yarra, we were both amazed how similar the challenges were. Gus made a comment that I often reflected on while representing the community at various town planning tribunal hearings over the pursuing decades. “If everyone gave a little bit of time to protect the amenity of their precinct, then the world would be a better place to live.” Thank you Gus for your wisdom, you were so correct.

Footnote: On another occasion Arnold Newman reminded me that it was one thing to photograph the famous, he had photographed American Presidents, noted actors and artists, but it is the quiet achievers that we must not forget as we record the fabric of society.

4 – Late in 1990 I was approached by New York-based publisher B. Martin Pedersen to write a foreword for the prestigious international annual Graphis Photo for inclusion in the 1991 edition.

At the time my association with the publication had spanned 15 years and had included the use my images to promote an earlier year’s international Call for Entries (in three languages).

I had the pleasure of meeting the previous, founding publisher, Walter Herdeg at his Swiss office, in 1975.

In writing the foreword for Graphis Photo91, I had the privilege of being the first non-European or American based photographer to do so. I commenced my essay with the following, “Shock from down under, I feel like the waiter at the Last Supper being asked to write the introduction to the Bible.”

5 – In 1994 I was approached to become the Patron to the newly formed Society of Advertising Commercial & Magazine Photographers (ACMP)

A position that I held from the ACMP’s inception until its demise in 2015.

The ACMP had one major charter that appealed to me. After some twenty years of fragmentation the profession now had a united body that worked to promote professional standards.

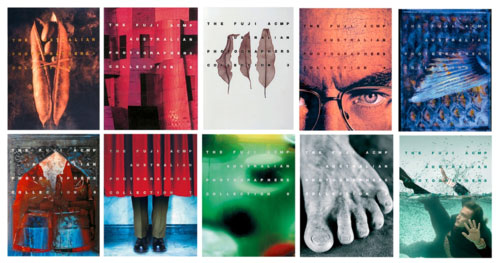

Aided by a small band of dedicated colleges we were able to negotiate a lucrative sponsorship deal with Hanimex Australia. The contact for one million dollars over ten years was signed and THE FUJI/ACMP AUSTRALIAN PHOTOGRAPHERS COLLECTION became a reality. The objective was to hold an annual exhibition of the best 150 images. A judging panel of the country’s most esteemed professionals, both photographers and buyers of photography were assembled annually. There were to be no prizes, every selected image was deemed a winner.

The contract with Hanimex was solely to conduct the annual judging and exhibit the work. However, the ACMP Board saw the benefit of producing a hard cover book and promoting the profession internationally. With limited funds I set about negotiating a deal with a respected book publishing company and enlisted the assistance of the internationally acclaimed design studio Cato Design. The principal Ken Cato had been a client and friend since the late 1960’s. It proved to be a successful partnership with only one downside, I announced to the Cato Design staff, at a gathering in their office that I would be unable to accept any further personal commissions from them! In my position as Patron I had to avoid any perceived conflict of interest. (I should mention that in the pursuing years, during the inevitable political skullduggery that occurs, various individuals did accuse me of continuing to work for Cato Design. Funny how certain individuals can’t contain themselves and throw mud without firstly substantiating the facts!).

It soon became obvious that an editor for the book was hard to find. The enormity of the work required with limited or no remuneration became an issue, hence by default I became the Editor (without remuneration) I thank my family and personal staff members for their understanding and assistance over the pursuing decade.

6 – Lastly, I suppose I should mention the Santa Pissing Christmas Cards.

As I remember saying to my assistants over the years, this is the worst client we have to deal with! … me.

Having spent considerable time travelling through Europe and America in 1975, in search of the next move in my career I met many leading international photographers and their agents. One thing that continually stood out was the need for self-promotion material and the need for networking. There was continual demand on photographers to produce personal direct mail material, something that their agents encouraged in what was a very competitive environment.

Returning to Melbourne I remained aware of the importance of being seen on the world stage and having my work published in international publications such as Photo-Graphis and Rotovision’s Art Directors’ Index to Photographers

Throughout the 1980’s I had commented on how bad most Christmas cars were and that Christmas had become over-commercialised.

In 1989 an agency Creative Director approached me and asked if I could assemble a team of twelve leading Australian photographers to produce a calendar for an automotive client. I obliged on condition that I could secure the month of December. ‘Hay Plains. 1989’ became the first in a series that continued for the next fifteen years.

Not only did the cards prove to be a unique, personal form of self-promotion, they also created a collection of stories as the years unfolded. Each year 1,000 cards were printed, personally scribed and distributed to my international client base.

In the late 1990’s I received a film production brief from an overseas client that I had not seen or spoken to for several years. On winning the global bid and working in the client’s hometown I was pleasantly surprised to see the framed collection of my cards that adorned the office wall. No other material was hanging on the walls, just my annual Christmas cards!

I continue to be surprised by the number of individuals that tell me that they have retained their collection of the cards.

What changes have you seen in the Photography industry since starting out. The good, the bad and the ugly?

Over the past half a century the dance has never changed, the music has often been re-gigged, but the steps remain the same. At the end of the day the task of ensuring that the dance continues, and the participants enjoy a memorable experience and perfect the technique should be all that matters. Photography has always been about individuals capturing images.

What has changed is the fact that now the masses can own a point-and-shoot capture device (smart phone etc.) and see themselves as photographers. There has always been more to photography than simply using a device, albeit a high-end camera, a smart phone or a cardboard box. To achieve a good photograph the image-maker must have street-smarts for what is required. Unfortunately the odd punter manages to fluke an occasional good image, however those individuals often find it too hard to withstand the professional rigors require to become a successful photographer. They have the ability to sing one song but find it hard to perform another.

Sadly and more importantly, the carefree and uninhibited days where one could experiment with every assignment appear to be a thing of the past!

Tell us about your archives you are working on?

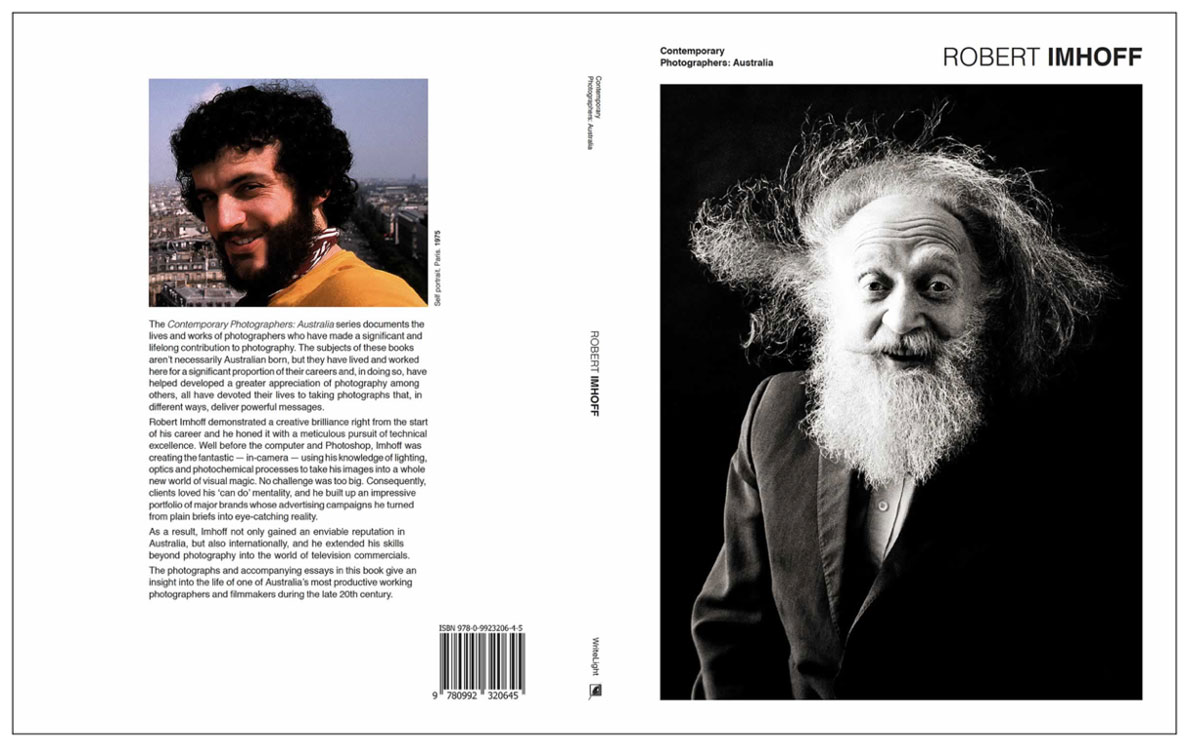

Working on my archive is a never-ending story. Following a stroke in 2004 my Occupational Therapist (OT) suggested that I need to find a project to work on as part of my rehabilitation. Coincidently I had been approached by WriteLight, the publishers of the Contemporary Photographers Australia series and ask to submit material for a book. The Occupational Therapist thought that the time spent sorting my vast archive would be an appropriate project for me to take on board.

As a consequence of the book, I received an offer from the Art Gallery of Ballarat to hold the retrospective exhibition Imhoff: a life of grain & pixels in 2014. I was humbled by the opportunity and thrilled that my friend Michael Shmith, the son of one of my early mentors, Athol Shmith agreed to open the exhibition and launch the book.

I was fortunate to have Inside Art’s Michel Lawrence interview me at the Art Galley of Ballarat during the exhibition. The Ballarat exhibition had been assembled from work that had already been archived. It represented only a select portion of my entire archive. The never-ending story continues!

What would your advice be to someone wanting to break into the Photography industry in the future?

With the expansion and availability of simplistic capture devices, longevity will be made easier for those that expand their knowledge base. The myriad of short cut applications that are now available, are no substitute for the substance of craftmanship. Ones skills must be honed to survive in this very competitive profession.

In the 1970’s a majority of photographers, when asked to create an image with soft light, simple adapted a readily available ‘Softar’ filter to their lens. Bingo in an instant they had achieved a soft look. They had taken the easy path while I elected to take the harder path. Having been fascinated by the physics of light, I elected to create soft light. To do so one must understand the behaviour of light and the power of refraction and reflection. I would spend endless hours and at times days experimenting with light and how I could master its use. I was often seen in fabric stores searching for the correct neutral fabric texture that I could use to scrim my light sources. Authentic soft light allows one to attain an image with a degree of sharpness, albeit softly lit sharpness. While a ‘Softar’ filter obliterates sharpness and simply creates a soft-focus image.

A friend who was one of my early life-mentors, was the Australian middle-distance runner John Landy. I have vivid memories of Landy telling me in my youth, that the main reason that allowed him to conquer the world was simply the fact that he ran more miles in training than his opponents. Photography is very similar, the more you train (practice) the easier it is to achieve success. I have found over the decades that the majority of photographers take the easy path while those that are successful, have always dug-deep and taken the hard road. Very few if any have been gifted, they have all faced-up to the mountain and conquered it.

An understanding and appreciation for history is a vital component. To move forward, an individual must grasp the past, study the hardships of the road already travelled and then the way forward will become much easier.

For more on the Imhoff archive visit: www.imhoffarchive.com

Share it around…